Fragile and beautiful odalisques

Source: Arnold Bennett, extract from ‘Russian Imperial Ballet at the Opera’ in Paris Nights, and Other Impressions of Places and People (New York: George H. Doran, 1913), pp. 68-78

Production: Mikhail Fokine, Cléopâtre and Schéhérazade, Palais Garnier, Paris, 1910

Text: I looked over the crimson plush edge of the box down into Egypt, where Cleopatra was indulging her desires; into a civilisation so gorgeous, primitive, and far-off that when compared to it the eighteenth and the twentieth centuries seemed as like as two peas in their sophistication and sobriety. Cleopatra had set eyes on a youth, and a whim for him had taken her. By no matter what atrocious exercise of power and infliction of suffering, that whim had to be satisfied on the instant. It was satisfied. And a swift homicide left the Queen untrammelled by any sentimental consequences. The whole affair was finished in a moment, and the curtain falling on all that violent and gorgeous scene. In a moment this Oriental episode, interpreted by semi-Oriental artists, had made all the daring prurient suggestiveness of French comedy seem timid and foolish. It was a revelation. A new standard was set, and there was not a vaudevillist in the auditorium but knew that neither he nor his interpeters could ever reach that standard. The simple and childlike gestures of the slave-girls as with their bodies and their veils they formed a circular tent to hide Cleopatra and her lover – these gestures took away the breath of protest.

Les sylphides

The St. Petersburg and the Moscow troupes, united, of the Russian Imperial Ballet, had been brought to Paris, at vast expense and considerable loss, to present this astounding spectacle of mere magnificent sanguinary lubricity to the cosmopolitan fashion of Paris. There the audience actually was, rank after rank of crowded toilettes rising to the dim ceiling, young women from the Avenue du Bois and young women from Arizona, and their protective and possessive men. And nobody blenched, no body swooned. The audience was taken by assault. The West End of Europe was just staggered into acceptance. As yet London has seen only fragments of Russian ballet. But London may and probably will see the whole. Let there be no qualms. London will accept also. London might be horribly scared by one-quarter of the audacity shown in Cleopatra, but it will not be scared by the whole of that audacity. An overdose of a fatal drug is itself an antidote. The fact is, that the spectacle was saved by a sort of moral nudity, and by a naïve assurance of its own beauty. Oh! It was extremely beautiful. It was ineffably more beautiful than any other ballet I had ever seen. An artist could feel at once that an intelligence of really remarkable genius had presided over its invention and execution. It was masterfully original from the beginning. It continually furnished new ideals of beauty. It had drawn its inspiration from some rich fountain unknown to us occidentals. Neither in its scenery, nor in its grouping, nor in its pantomime was there any clear trace of that Italian influence which still dominates the European ballet. With a vengeance it was a return to nature and a recommencement. It was brutally direct. It was beastlike; but the incomparable tiger is a beast. It was not perverse. It was too fresh, zealous, and alive to be perverse. Personally I was conscious of the most intense pleasure that I had experienced in a theatre for years. And this was Russia! This was the country that had made such a deadly and disgusting mess of the Russo-Japanese War.

The box was a stage-box. It consisted of a suite of two drawing-rooms, softly upholstered, lit with electric light, and furnished with easy-chairs and mirrors. A hostess might well have offered tea to a score of guests therein. And as a fact there were a dozen people in it. Its size indicated the dimensions of the auditorium, in which it was a mere cell. The curious thing about it was the purely incidental character of its relation to the stage. The front of it was a narrow terrace, like the mouth of a bottle, which offered a magnificent panorama of the auditorium, with a longitudinal slice of the stage at one extremity. From the terrace one glanced vertically down at the stage, as at a street-pavement from a first-storey window. Three persons could be comfortable, and four could be uncomfortable, on the terrace. One or two more, by leaning against chair backs and coiffures, could see half of the longitudinal slice of the stage. The remaining half-dozen were at liberty to meditate in the luxurious twilight of the drawing-room. The Republic, as operatic manager, sells every night some scores, and on its brilliant nights some hundreds, of expensive seats which it is perfectly well aware give no view what

ever of the stage: another illustration of the truth that the sensibility of the conscience of corporations varies inversely with the size of the corporation.

The unforgettable season

But this is nothing. The wonderful aspect of the transaction is that purchasers never lack. They buy and suffer; they buy again and suffer yet again; they live on and reproduce their kind. There was in the hinterland of the box a dapper, vivacious man who might (if he had wasted no time ) have been grandfather to a man as old as I. He was eighty-five years old, and he had sat in boxes of an evening for over sixty years. He talked easily of the heroic age before the Revolution of ’48, when, of course, every woman was an enchantress, and the farces at the Palais Royal were really amusing. He could pipe out whole pages of farce. Except during the entr’actes this man’s curiosity did not extend beyond the shoulders of the young women on the terrace. For him the spectacle might have been something going on round the corner of the next street. He was in a spacious and discreet drawing-room; he had the habit of talking; talking was an essential part of his nightly hygiene; and he talked. Continually impinging, in a manner fourth-dimensional, on my vision of Cleopatra’s violent afternoon, came the “Je me rappelle” of this ancient. Now he was in Rome, now he was in London, and now he was in Florence. He went nightly to the Pergola Theatre when Florence was the capital of Italy. He had tales of kings. He had one tale of a king which, as I could judge from the hard perfection of its phraseology, he had been repeating on every night-out for fifty years. According to this narration he was promenading the inevitable pretty woman in the Cascine at Florence, when a heavily moustached person en civil flashed by, driving a pair of superb bays, and he explained not without pride to the pretty woman that she looked on a king.

“It is that, the king?” exclaimed the pretty ingénue too loudly.

And with a grand bow (of which the present generation has lost the secret) the moustaches, all flashing and driving, leaned from the equipage and answered: “Yes, madame, it is that, the king.

“Et si vous aviez vu la tête de la dame…!” In those days society existed.

I should have heard many more such tales during the entr’acte, but I had to visit the stage. Strictly, I did not desire to visit the stage, but as I possessed the privilege of doing so, I felt bound in pride to go. I saw myself at the great age of eighty-five recounting to somebody else’s grandchildren the marvels that I had witnessed in the coulisses of the Paris Opéra during the unforgettable season of the Russian Imperial Ballet in the early years of the century, when society existed.

At an angle of a passage which connects the auditorium with the tray (the stage is called the tray, and those who call the stage the stage at the Opéra are simpletons and lack guile) were a table and a chair, and, partly on the chair and partly on the table, a stout respectable man: one of the twelve hundred. He looked like a town-councillor, and his life-work on this planet was to distinguish between persons who had the entry and persons who had not the entry. He doubted my genuineness at once, and all the bureaucrat in him glowered from his eyes. Yes! My card was all right, but it made no mention of madame. Therefore, I might pass, but madame might not. Moreover, save in cases very exceptional, ladies were not admitted to the tray. So it appeared! I was up against an entire department of the State. Human nature is such that at that moment, had some power offered me the choice between the ability to write a novel as fine as Crime and Punishment and the ability to triumph instantly over the pestilent town-councillor, I would have chosen the latter. I retired in good order. “You little suspect, town-councillor,” I said to him within myself, “that I am the guest of the management, that I am extremely intimate with the management, and that, indeed, the management is my washpot!” At the next entr’acte I returned again with an omnipotent document which instructed the whole twelve hundred to let both monsieur and madame pass anywhere, everywhere. The town-councillor admitted that it was perfect, so far as it went. But there was the question of my hat to be considered. I was not wearing the right kind of hat! The town councillor planted both his feet firmly on tradition, and defied imperial passports. “Can you have any conception,” I cried to him within myself, “how much this hat cost me at Henry Heath’s?” Useless! Nobody ever had passed, and nobody ever would pass, from the auditorium to the tray in a hat like mine. It was unthinkable. It would be an outrage on the Code Napoléon…. After all, the man had his life-work to perform. At length he offered to keep my hat for me till I came back. I yielded. I was beaten. I was put to shame. But he had earned a night’s repose.

* * * * * *

The famous, the notorious foyer de la danse was empty. Here was an evening given exclusively to the ballet, and not one member of the corps had had the idea of exhibiting herself in the showroom specially provided by the State as a place or rendezvous for ladies and gentlemen. The most precious quality of an annual subscription for a seat at the Opéra is that it carries with it the entry to the foyer de la danse (provided one’s hat is right); if it did not, the subscriptions to the Opéra would assuredly diminish. And lo! the gigantic but tawdry mirror which gives a factitious amplitude to a room that is really small, did not reflect the limbs of a single dancer! The place had a mournful, shabby genteel look, as of a resort gradually losing fashion. It was tarnished. It did not in the least correspond with a young man’s dreams of it. Yawning tedium hung in it like a vapour, that tedium which is the implacable secret enemy of dissoluteness. This, the foyer de la danse, where the insipidly vicious heroines of Halévy’s ironic masterpiece achieved, with a mother’s aid, their ducal conquests! It was as cruel a disillusion as the first sight of Rome or Jerusalem. Its meretriciousness would not have deceived even a visionary parlour-maid. Nevertheless, the world of the Opéra was astounded at the neglect of its hallowed foyer by these young women from St. Petersburg and Moscow. I was told, with emotion, that on only two occasions in the whole season had a Russian girl wandered therein. The legend of the sobriety and the chastity of these strange Russians was abroad in the Opéra like a strange, uncanny tale. Frankly, Paris could not understand it. Because all these creatures were young, and all of them conformed to some standard or other of positive physical beauty! They could not be old, for the reason that a ukase obliged them to retire after twenty years’ service at latest; that is, at about the age of thirty-six, a time of woman’s life which on the Paris stage is regarded as infancy. Such a ukase must surely have been promulgated by Ivan the Terrible or Catherine!… No! Paris never recovered from the wonder of the fact that when they were not dancing these lovely girls were just honest misses, with apparently no taste for bank-notes and spiced meats, even in the fever of an unexampled artistic and fashionable success.

An honest miss

Amid the turmoil of the stage, where the prodigiously original peacock-green scenery of Scheherazade was being set, a dancer could be seen here and there in a corner, waiting, preoccupied, worried, practising a step or a gesture. I was clumsy enough to encounter one of the principals who did not want to be encountered; we could not escape from each other. There was nothing for it but to shake hands. His face assumed the weary, unwilling smile of conventional politeness. His fingers were limp.

“It pleases you?”

“Enormously.”

I turned resolutely away at once, and with relief he lapsed back into his preoccupation concerning the half-hour’s intense emotional and physical labour that lay immediately in front of him. In a few moments the curtain went up, and the terrific creative energy of the troupe began to vent itself. And I began to understand a part of the secret of the extreme brilliance of the Russian ballet.

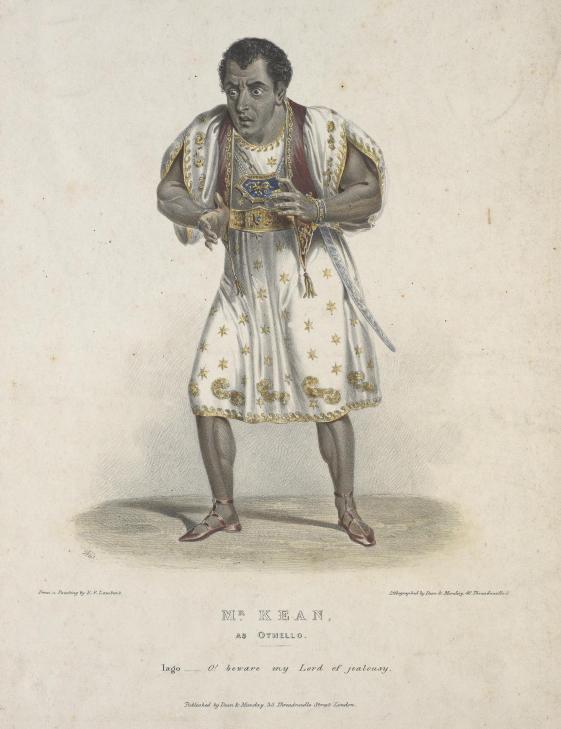

Chief eunuch

The brutality of Scheherazade was shocking. It was the Arabian Nights treated with imaginative realism. In perusing the Arabian Nights we never try to picture to ourselves the manners of a real Bagdad; or we never dare. We lean on the picturesque splendour and romantic poetry of certain aspects of the existence portrayed, and we shirk the basic facts: the crudity of the passions, and the superlative cruelty informing the whole social system. For example, we should not dream of dwelling on the more serious functions of the caliphian eunuchs. In the surpassing fury and magnificence of the Russian ballet one saw eunuchs actually at work, scimitar in hand. There was the frantic orgy, and then there was the barbarous punishment, terrible and revolting; certainly one of the most sanguinary sights ever seen on an occidental stage. The eunuchs pursued the fragile and beautiful odalisques with frenzy; in an instant the seraglio was strewn with murdered girls in all the abandoned postures of death. And then silence, save for the hard breathing of the executioners!… A thrill! It would seem incredible that such a spectacle should give pleasure. Yet it unquestionably did, and very exquisite pleasure. The artists, both the creative and the interpretative, had discovered an artistic convention which was at once grandiose and truthful. The passions displayed were primitive, but they were ennobled in their illustration. The performance was regulated to the least gesture; no detail was unstudied; and every moment was beautiful; not a few were sublime.

Scheherazade

And all this a by-product of Russian politics! If the politics of France are subtly corrupt; if any thing can be done in France by nepotism and influence, and nothing without; if the governing machine of France is fatally vitiated by an excessive and unimaginative centralisation — the same is far more shamefully true of Russia. The fantastic in efficiency of all the great departments of State in Russia is notorious and scandalous. But the Imperial ballet, where one might surely have presumed an intensification of every defect (as in Paris), happens to be far nearer perfection than any other enterprise of its kind, public or private. It is genuinely dominated by artists of the first rank; it is invigorated by a real discipline; and the results achieved approach the miraculous. The pity is that the moujik can never learn that one, at any rate, of the mysterious transactions which pass high up over his head, and for which he is robbed, is in itself honest and excellent. An alleviating thought for the moujik, if only it could be knocked into his great thick head! For during the performance of the Russian Imperial Ballet at the Paris Opéra, amid all the roods of toilettes and expensive correctness, one thinks of the moujik; or one ought to think of him. He is at the bottom of it. See him in Tchekoff’s masterly tale, The Moujiks, in his dirt, squalor, drunkenness, lust, servitude, and despair! Realise him well at the back of your mind as you watch the ballet! Your delightful sensations before an unrivalled work of art are among the things he has paid for.

Comments: Arnold Bennett (1867-1931) was a British novelist and playwright. He lived in Paris from 1902 to 1912. In 1910 he saw the ballets Cléopâtre and Schéhérazade (based on Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s music), choreographed by Mikhail Fokine and performed by the Ballet Russes. Sergei Diaghilev formed the touring company out of members of the The Mariinsky Ballet, or Imperial Russian Ballet, in 1909. It became known as the Ballet Russes the following year. The illustrations by E.A. Rickards, with their captions, come from Bennett’s book.

Links: Copy at Hathi Trust