“George Almar as Carnaby Cutpurse in ‘The Cedar Chest'” (1834), attributed to Robert William Buss, University of Bristol Theatre Collection via Art UK

Source: Westland Marston, Our Recent Actors: being recollections critical, and, in many instances, personal, of late distinguished performers of both sexes (Boston: Roberts brothers, 1888), pp. 2-8

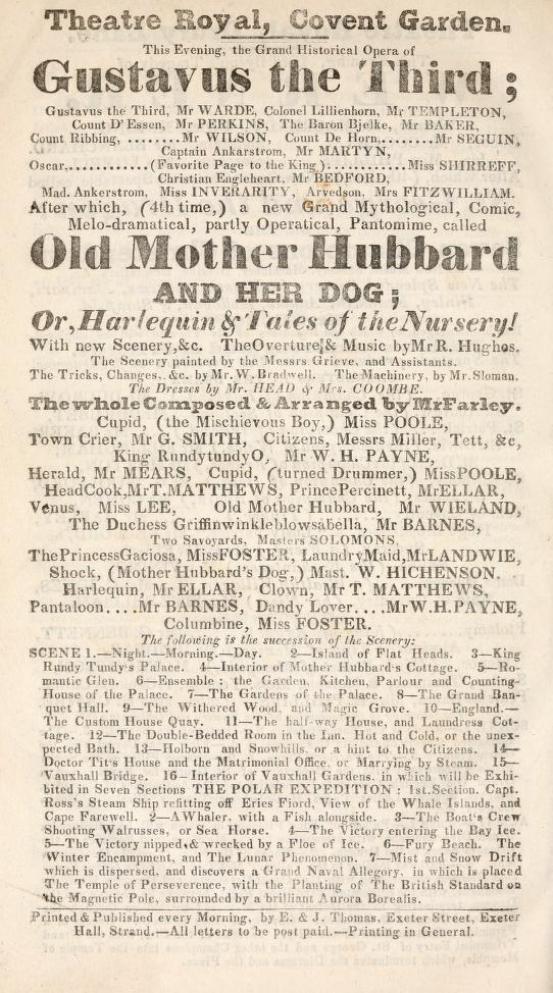

Production: Possibly George Almar, The Cedar Chest; or, The Lord Mayor’s Daughter, Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London, July 1834

Text: To speak in the first person, which, spite of its necessary egotism, is the most convenient form of narrative, I came from the Lincolnshire seaport and market-town of Great Grimsby to London in the year 1834, having at that time attained my fifteenth year. It had been arranged that I should be articled to my uncle, a solicitor, who, with his partner, had offices near Gray’s Inn. The partner’s house was my first abode, and here I found—or perhaps I should say, took—more liberty of action during my evenings than was quite suitable in the case of so mere a boy.

Two years previously, on my first visit to London, I had been arrested by the playbills of the great patent theatres and by the magical name—then still a sound of lingering greatness—of Edmund Kean. “Drury Lane!” “Covent Garden!” “Mr. Kean!” Strange how these words of romance had some way penetrated to me through the seclusion of a “serious” home in the country, where my excellent parents never mentioned the stage, except to warn me, or others, of its dangers and seductions. Now that at a too early age I was, in many respects, my own master, and could indulge, if I chose, my longing to visit a theatre, I began to ask myself what there was in dramatic performances that should make them necessarily objectionable. I recalled my own annual displays when, as a lad of eleven or twelve, I had appeared with my schoolmates at the Theatre Royal, Great Grimsby, in various dramatic characters, at one time sustaining on “breaking-up day” the part of Juba in “Cato,” and another that of Electra in the tragedy of “Sophocles,” and afterwards that of Miriam (the Christian convert) in Milman’s “Jerusalem Delivered.” I remembered, too, how much my father, a zealous lover of Sophocles, though a foe to the stage, had praised my rendering of Electra. Was it possible, I argued, that a mode of composition allowable and, indeed, admirable in Greek, should be censurable in English, or that dialogue which was innocent when read should become injurious when spoken in public, with dresses and scenery to assist the impression? If the theatre might have its bad side, so also had literature, art, and even trade. If no judicious parent would put “Tom Jones” into a boy’s hands, was that a reason for withholding the novels of Scott? Must “Don Quixote” be forbidden because the word “fiction” applied also to “Gil Bias”? With this kind of logic I extorted a reluctant permission from my conscience for an act which, if allowable in itself, was still one of grave disobedience towards affectionate parents. I can still recall the boyish sophistry which prompted me to choose Sadler’s Wells Theatre for my first visit. It was a small theatre, and it was situated in a suburb—facts which, as they were likely to diminish my pleasure, seemed in the same degree to make my transgression a slight one. I might have gone to Covent Garden, I reasoned, and, at that renowned theatre, have revelled in the best acting of the day, whereas I self-denyingly contented myself with Sadler’s Wells. On the night when I entered that (to me) enchanted palace, I found there a new opiate for my restless conscience. The title of the piece represented I quite forget, but its main situation is as fresh as ever in my memory. A girl, deeply attached to her betrothed, learns his life is at the mercy of a villain (of course, an aristocrat), whom she has inspired with a lawless passion. She implores his pity for her lover, only to find that the sacrifice of her honour is the price of his ransom. I remember how my heart came into my throat and the tears into my eyes when the noble-minded girl, striking an attitude of overwhelming dignity, before which the wretch naturally abased himself, spurned his offer, and committed her cause to that Providence which, in the good, honest melodrama of that day, never delayed to vindicate the trust reposed in it. What most comforted me during the evening was the conviction that my father, could he have seen the piece, would heartily have applauded it and recanted at once his unqualified enmity to the theatre. I fancied how cordially, had he been behind the scenes, he would have shaken hands with Miss Macarthy (afterwards Mrs. R Honner), who had no inconsiderable skill in painting the struggles of virtuous heroines. I might certainly, however, have trembled for the consequences had he encountered a certain Mr. G. Almar, who, if my memory serves me, personated the miscreant of the drama.

I was curious enough, even on the first night of attending a theatre, to ask myself why Mr. Almar made such incessant use of his arms. Now they were antithetically extended, the one skyward, the other earthward, like the sails of a windmill; now they were folded sternly across his bosom; now raised in denunciation; now clasped in entreaty, and considerately maintained in their positions long enough to impress the entire audience at leisure with the effect intended. I was critical enough to ask myself whether the more heroic attitudes of this gentleman would not have been heightened by the contrast of occasional repose, and whether there were, in his opinion, any fatal incompatibility between easy and natural gestures and effective acting. On quitting the theatre, my inquiring mind received some light upon these points, for in the window of a confectioner, who was also a theatrical printseller, my attention was arrested by coloured portraits of local, or other stage favourites, in their principal characters. Here figured “Mr. Cobham, as Richard the Third,” with a frown to spread panic through the ranks of “Shallow Richmond.” Here was Mr. T. P. Cooke, as William in “Black-eyed Susan,” in that renowned hornpipe which illustrates William’s happier days, ere Susan and he had dreams of a court-martial. And here figured my friend of “The Wells,” Mr. G. Almar, in various characters, in all of which the use of his arms was so remarkable, that it might easily be inferred he acted less for the sake of his general audience than for that of the artist who depicted him, and who probably would have thought little of an actor who did not supply him with attitudes. I was glad, moreover, to find from one of the prints that Mr. Almar’s arms were not always employed to illustrate sinister characters, but that on occasions they could be virtuously engaged. In this particular instance they represented the action of the noble Bella in “Pizarro,” as he bears Cora’s rescued child triumphantly over the cataract.

Comments: John Westland Marston (1819-1890) was a British dramatist and critic, the son of a dissenting minister. Our Recent Actors in an autobiographical account of the stage performances he had witnessed. Sadler’s Wells Theatre was at a low point in its fortunes in the 1830s, located on the rural fringes of London and struggling to compete with the three patent theatres (Covent Garden Drury Lane, Haymarket). The manager at this time was the actor George Almar. A later manager was Robert Honner, who married the actress Maria Macarthy (1812-1870). The melodrama Marston saw was possibly The Cedar Chest; or, The Lord Mayor’s Daughter, written by Almar, which featured him in the lead male role alongside Maria Macarthy.

Links: Copy at Hathi Trust